THE OLDEST BROTHER

In the Biblical panoply, Reuben, Jacob’s oldest son, is not one of the leading lights.

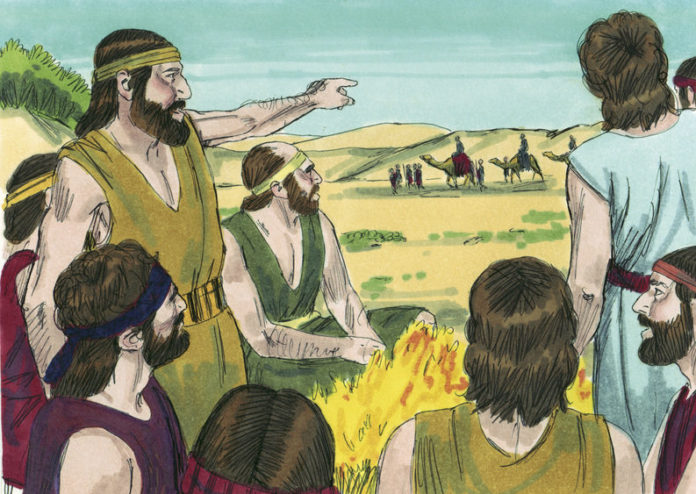

He played a significant role in the fate of his younger brother Joseph. When the other brothers decided that Joseph had to be disposed of, Reuben succeeded in preventing the murder. But we wonder what his real feelings were.

Deep down, did he share the brothers’ animosity to Joseph, and simply intervene to prevent bloodshed?

The explanation the Torah gives really leaves the question in limbo. It says Reuben wanted “to deliver him from their hand and to get him back to their father” (Gen. 37:22).

It sounds like a good idea but maybe it is only a delaying tactic. In Reuben’s mind it might have diffused the ugly situation, but it was only a temporary ploy as we see from the fact that when Reuben went looking for Joseph he couldn’t find him.

Reuben and the brothers had agreed that instead of killing Joseph they would put him in a pit (where, according to the sages, there were scorpions and snakes – not a pleasant prospect at the best of times).

While Reuben’s attention was diverted, the brothers had taken Joseph out of the pit and sold him to a caravan of passers-by. If Reuben had really been determined to save Joseph, surely he would have looked for an empty pit that had no snakes and scorpions, and he would have stood guard until the brothers went off on some other errand. So again we wonder about Reuben’s motives.

The rabbis are not sure how to treat Reuben’s actions or lack of them. Some say that what diverted Reuben’s attention was that he needed to go and daven; others say that when there is an emergency to life or health, it overrides normal religious practices.

There is no one complete answer, but at least some credit must be given to Reuben for trying.

WALKING, STANDING & SITTING

The sidra is entitled “Vayyeshev”, “And he sat”. The context actually requires the translation, “And he settled”.

Linguistically the two versions are connected even though we would normally say that “to sit” is a temporary action while “to settle” implies a longer time-frame.

Leaving that problem to the lexicographers, we can go off on a tangent and look at the beginning of the Book of Psalms.

Psalm 1 contrasts the righteous person with the wicked. The tzaddik is called “ashrei”, “happy”.

Samson Raphael Hirsch has a more sophisticated approach. Linking the root “aleph-shin-resh” to a word that means to step out, he tells us that “ashrei” indicates a person who has a direction in life.

The Psalmist says that the person who is “ashrei” is challenged by three actions – how to walk, how to stand and how to sit.

Unlike the rasha, the tzaddik does not walk in wicked ways, he does not pause in places where the sinners stand, and he does not sit where the mockers meet.

In the course of his life’s journey the good person steps forward (‘walks”); on the way he does not let himself slow down or stop in exciting or inciting places which threaten to entrap him in evil and sin.

WHAT MADE HIM A TZADDIK

Jewish tradition bestowed a great accolade upon Joseph. It called him “Yosef HaTzaddik” – Joseph the Righteous.

Why this honour came his way has nothing to do with his ability to interpret dreams or the fact that years later he gave his family a new lease of life when he settled them in Egypt.

The incident that evoked the title was his refusal to be tempted by the wife of Potiphar; he refused and said, “How can I do such a wicked thing and sin against God?” (Gen. 39:8-9).

One might think that succumbing to the woman’s wishes would have been a sin against her husband Potiphar, and that God did not come into it.

In truth, both she and Joseph would have committed a sin against Potiphar, and Joseph recognised this even if the woman did not.

But what Joseph’s words tell us is that human conscience is answerable to God, not only to earthly beings or human considerations. Commit a sin against a human being and you also betray God who made you and is the ultimate, objective judge of right and wrong.

The 20th century proves this principle. So many regimes have followed the maxim, “God is dead – therefore everything is allowed”.

But if God is toppled from his throne, there is no judge to judge the judges, no ruler to overrule the rulers. There is no eternal standard of right and wrong; they become purely matters of opinion, and no-one is safe any more.

Does that mean that an atheist or agnostic cannot be ethical? Not at all, but they are living on the ethical capital of previous generations and sooner or later it will be used up.

Belief in God, however, with its insistence on truth, justice and peace constantly reminds us of ethical ideals, gives them authority and objectivity, and warns us that whatever we do there will be an account and reckoning.