The Board of Deputies has slammed Trade Union backing for a pro-Palestinian march in central London on the same weekend as the Balfour Declaration Centenary commemorations on Saturday, November 4.

Synagogues will host celebrations of the 100th anniversary in a special Balfour Shabbat.

The National Union of Teachers, Unison, GMB, Aslef and Unite The Union are displaying support for the Justice Now: Make It Right For Palestine demonstration.

Board president Jonathan Arkush has lambasted the union movement decision to back the march.

“If these groups had spent the last 100 years making the positive case for Palestine that we make for Israel there might now be two states living side by side and in peace,” he noted.

“While they mope out in the cold, we’ll be celebrating the Balfour Centenary in upbeat events right across the country. They should reflect on this as they continue their doomed campaign of rejectionism and negativity.”

The Palestinian Solidarity Campaign, Stop The War Coalition, Friends of Al Aqsa and Muslim Association Of Britain have organised the contentious rally.

Literature for the march uses official logos of the trade unions stating ‘For the past 100 years Palestinian rights have been disregarded. As we approach the centenary of the Balfour Declaration – on the 2nd November – which built the path for their dispossession, we are demanding justice and equal rights for Palestinians now.’

Speakers include anti-Zionists John Pilger, Tariq Ali and Matt Wrack, general secretary of the Fire Brigades Union.

Historically, the 1917 Balfour Declaration enshrined the British Government’s support for a Jewish national home.

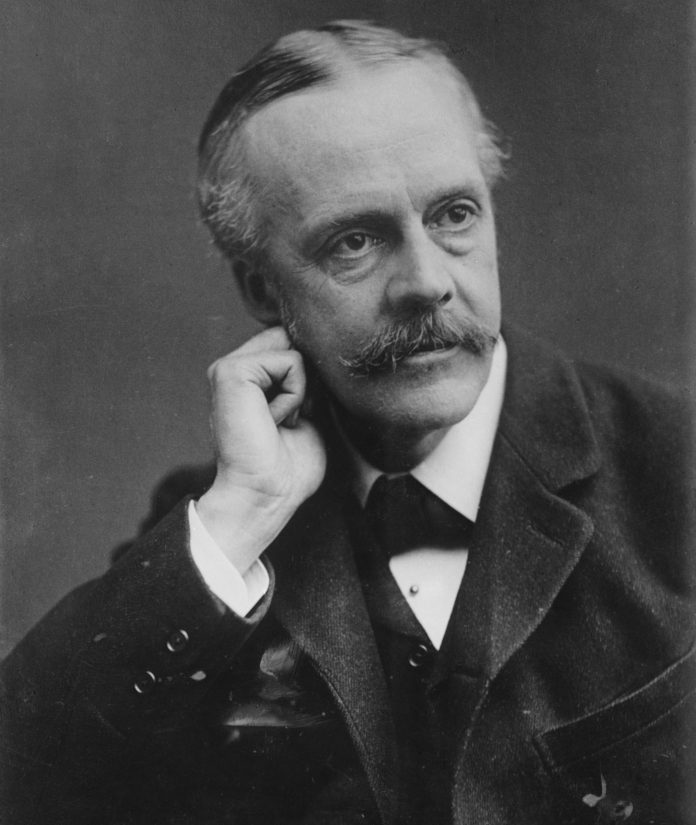

Originally taking the form of a letter from British Foreign Minister Lord Balfour to honorary president of the Zionist Federation Lord Rothschild, the Declaration played an important role in Britain’s support for and creation of the State of Israel.

To mark the Centenary of this landmark document, BICOM has produced a briefing explaining the Declaration, outlining its historical context, its legal implications and why the Declaration continues to hold significance 100 years later.

Bicom key points:

Zionism, the name given to the national liberation movement of the Jewish people, emerged in Europe at the end of 19th century and called for the establishment of a Jewish homeland in the Land of Israel/Palestine. By 1917, when the Balfour Declaration was published, Zionism had cross-party support in Britain as well as government backing in France, America, and other countries, while the pending defeat of the Ottoman Empire – which had controlled that geographic area for the previous four hundred years – provided an opportunity for British politicians to translate their ideological support for Zionism into practice. In that period, the Zionist movement’s call for statehood was but one of many nationalist movements – such as the Arab, Turkish, Armenian, and Kurdish – which saw the collapse of empires as an opportunity to achieve self-determination.

The Declaration neither signalled the start of a Jewish return to the Land of Israel/Palestine nor mass immigration to it. Jews had enjoyed a continuous presence in the area for centuries before the destruction of the Second Jewish Temple in 70 CE, and by the time of the Declaration, approximately 80,000-90,000 Jews already lived in Palestine without the assistance of any external power.

Despite opposition among many locals to Jewish immigration, some Middle Eastern leaders welcomed Zionism. As Emir Faisal ibn Husain, leader of the Arab delegation at the Paris Peace Conference wrote, the Arabs “look with the deepest sympathy on the Zionist movement” seeing it as helping their own people’s quest for self-determination.

The Declaration itself was not a legal document but the policy it expressed, the establishment of a Jewish national home in Palestine, became binding in international law following the 1920 San Remo Conference, and the 1922 British Mandate from the League of Nations. As the Mandate drew to a close, the international legitimacy of Jewish statehood was further strengthened by UN General Assembly Resolution 181 – which recommended partitioning Mandatory Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states – and reinforced by the State of Israel’s acceptance into the family of nations following its 1948 War of Independence.

While the Declaration constituted an important component in facilitating Jewish immigration and creating the legal basis for the establishment of the State of Israel, it did not make such a homeland inevitable. In fact, primarily motivated by an attempt to satisfy Arab opposition to Zionism, British White Papers in the 1920s and 1930s severely limited Jewish immigration and threatened the viability of Jewish statehood. Any analysis of Britain’s role in the establishment of Israel should thus include both the Declaration – which encouraged Jewish immigration – and the numerous White Papers which restricted it.

Britain’s role in the Middle East in the decades following the First World War was highly significant. But the history of the Declaration, the years of the British Mandate and the establishment of the State of Israel are complex and any assessment of Britain’s role needs to take that into consideration.