Bava Basra 21b discusses the case where someone wishes to operate a mill in an alley in which another person has an established mill. Rav Huna rules that the first establishment may prevent the newcomer from opening shop, as he will impinge on the first person’s livelihood. Rav Huna son of Rav Yehoshua argues that it is permitted, as people have free choice where to shop. He restricts his leniency to competitors from the same area. The gemora adds that even an outsider is permitted to compete if he pays local taxes. In the course of discussion, the gemora records that one may not set up a fishing net too close to another person’s net, to divert fish into his own net. As the fish were attracted to the first net, they are viewed as if they have already been acquired by that person. Most poskim rule like Rav Huna son of Rav Yehoshua without mentioning the fishing-net restriction, thus permitting most competition.

UNFAIR COMPETITION

Although we have said that poskim do not pasken like Rav Huna, Aviasaf , as known as ראבי”ה, cited by Mordechai (Bava Basra-516), forbids opening a store at the entrance to a dead-end alley if a similar establishment is already located further within the alley. Such competition is considered unfair, for it will ruin the inner business, as customers will first encounter the outer store. Beis Yosef holds that Aviasaf is following Rav Huna and since halacha does not follow that opinion, Shulchan Aruch ignores Aviasaf’s view. Rema holds that Aviasaf does follow Rav Huna ben Rav Yehoshua, but he would agree to prohibit opening a business at the start of a dead-end alley where it is bari hezeka, certain damage. Damage in this context does not refer to loss of profit, but to undermining the viability of the business to sustain the proprietor’s livelihood. It is not always easy to assess this, and since the primary source for this is a Teshuvas Rema (10), it is important to be aware of the historical details relating to that case.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

In Venice in 1549 an event occurred which plays a pivotal role in establishing halacha regarding competition. Rabbi Meir Katzenellenbogen of Padua wanted to print a new edition of Rambam’s Mishneh Torah. Although it had already been printed four times, most recently by Bomberg in 1524, he had made extensive textual corrections and added his own comments. There were only three printers in the world at that time printing rabbinical books: Parnas, Soncino’s successor, in Constantinople, sons of Gershon Cohen in Prague, and Giustiniani in Venice. In 1545, Marco Antonio Giustiniani of the family of Venetian patricians whose palaces still line the Grand Canal, had opened a Hebrew printing press. His master printer was Cornelius Adelkind, who also worked for Bomberg. During 1546-1551 Giustiniani produced a fine Shas edited by R’ Yehoshua Boaz (known for his Shiltei Hagibborim), incorporating his masterpiece glosses Massores Hashas, Ein Mishpat, Ner Mitzvah and Torah Or, which have enhanced our gemoras ever since. For whatever reason, Maharam Padua did not choose Giustiniani to print his work, and instead went into partnership with another Venetian nobleman Alvise Bragadini, establishing a new Hebrew press in 1550. Jews were not permitted to print themselves, so they partnered with Christian noblemen who were able to obtain the necessary permits. Scarcely had the sefer appeared when another edition of Rambam without Maharam’s notes, based on the earlier prints, was rushed onto the market by Giustiniani, priced at a gold coin less then Maharam’s – a substantial discount. The important point is that it was not a matter of copyright, but it was evident that Giustiniani had acted for the malicious purpose of eliminating the new competitor. Maharam turned to his talmid and relative Rabbi Moshe Isserles of Cracow (Rema). The case presented difficulties: a Jew and non-Jew in partnership had printed a book, and a Christian rival printed a similar book at the same time for the purpose of protecting his monopoly by ruining the first printer. The real sufferer was Maharam, whose entire fortune was invested in the enterprise and stood to lose everything. He could obtain no redress against the powerful nobleman in the Venetian courts and Beis Din could not assume jurisdiction to restrain the second printer. Rema had the indirect remedy of enjoining all Jews under cherem from purchasing the sefarim of Giustiniani.

TRAGIC OUTCOME

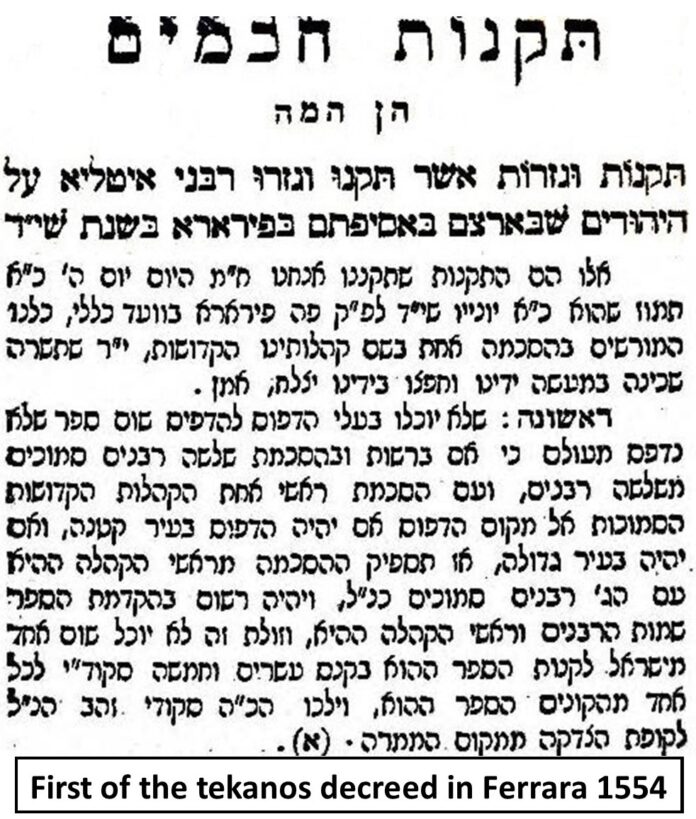

Rema had considered the ban’s danger to the spread of Torah literature, and the need to be grateful to Giustiniani for his excellent edition of the Talmud, but Rema viewed it as a commercial enterprise that would continue to profit from other sefarim after the ban. The vengeance of the proud and powerful nobleman was great, reasoning that if Bragadini could obtain a rabbinical ban against his books, why should he not get a papal opinion against his rival. Without wanting to compromise his own publications, he sought to find matters objectional to the Church in Maharam’s comments. He employed the services of apostate Jews, including Solomon Romano, grandson of the controversial Eliyahu Bachur (Elias Levita), who then used the opportunity to display their Christian zeal and went further, petitioning to have all Hebrew books burned. In August 1553 the pope issued a Bull directing the burning of the Talmud, and black-robed Inquisitors led police to search houses for Talmudic works. Books and manuscripts were carted to Campo di Fiori in Rome and publicly burned on Rosh Hashana 1553, reminiscent of the Talmud burning in Paris of 1242. The decree spread throughout Italy with the blaze of burning sefarim in all the cities, including Venice. Rema’s ban had caused Giustiniani’s business to fall off so that his presses closed in 1552. Because of the confiscation of all books, Bragadini press was also silenced in 1554, not resuming production until 1563, continuing to publish sefarim up to 1795. Following this tragic episode Maharam Padua presided over a conference of fourteen Italian Rabbonim and community leaders on 21st June 1554 in Ferrara. One of the nine takanos decreed was forbidding any sefer to be published without haskamos of three Rabbonim, to ensure no irresponsible statements would be printed which might upset Christians, with a penalty for any purchaser of unendorsed sefarim. This was the forerunner of later haskomos, except that approbations were adapted to target future publishers rather than purchasers, to protect against copyright infringement.

BARI HEZEKAH

Rema, in his teshuva, relied on Aviasaf, as his case clearly involved predatory pricing with the intention of forcing the business to close. In practice, competition may well hit the bottom line, but the question is to what extent it will affect the survival of the original business. Chassam Sofer (CM-61/118) also quoted Aviasaf as a precedent and asserts that the views permitting competition are only where the new store will decrease the profits of the original business, but not where it is impossible for it to survive. Rabbi Moshe Feinstein (IM-CM1:38) follows Chassam Sofer and rules that loss of livelihood is not defined as someone not able to put food on the table, but even taking away one’s ability to afford as much as the average person in his social class. Beis Efraim (CM26-27) rules against Aviasaf who permitted new hotels at the city gate despite them gaining an advantage over hotels inside the city. Many poskim are lenient regarding contemporary situations such as competing pizza stores on the same block, as there would often be enough demand for both to survive. Rabbonim may advise to vary the range of products offered, so customers will exercise their preference. However, that may not be the case in a small community where there is insufficient demand to support two stores. As there is no clear consensus, it would depend on the assessment of one’s Rav, especially as it is almost impossible for the person to be completely objective.

MARUFIA

Based on the gemora’s restriction of fishermen encroaching on another’s territory, there is a concept of ‘marufia’, an Arabic word meaning steady customer. Shulchan Aruch (CM-156) writes that custom varies but most poskim today rule that it is forbidden to lure away someone’s steady customer. There would be nothing to stop the customer from switching allegiance, subject to contractual commitments. However, if non-Jewish providers are attempting to take away someone’s customers, a Jewish competitor would be permitted to do the same, as those customers are not considered ‘in the net’.

YOM HASHUK

Our sugya discusses a city which has a Yom Hashuk, a market day when merchants from surrounding cities gather to buy and sell goods. On market day out-of-towners are permitted to compete with locals, as many additional customers come from outside the city. The situation of internet sales and home deliveries to all areas has effectively created a permanent ‘yom hashuk’ that is not specific to any location and therefore area limitations are hardly applicable nowadays. The superior rights of city taxpayers mentioned in the gemora are also irrelevant as those taxes gave shops trading rights which are not pertinent today (Chassam Sofer-CM79).