By Rabbi Jeremy Lawrence

As we get ready for Purim we are reminded of the villainy of Haman, who proclaimed that a certain people was dispersed throughout the provinces of Achashverosh, their laws different from every other people and who didn’t even respect the laws of the King. With this he was prepared to pay for and sought royal permission “leabdam”.

With a knowledge of the story we always translate the word as to destroy, but the word itself has a measure of ambiguity. To the ears of Achashverosh, it might have suggested “to have them lost” in Persian society, fully assimilated. As a distinct people, they would have been destroyed but alive and integrated. It may have been received as a reasonable proposition.

That this was not Haman’s agenda is evident from the proclamation that he then issues with the expanded language “to destroy, to slay and exterminate all Jews”. There is not a shred of ambiguity here. Haman’s guarded initial language presented him as a man concerned for the stability of the realm. Given authority, the strength of his racism becomes manifest.

February 24 this year marked the 75th anniversary of the sinking of the SS Struma, a ship carrying approximately 790 Jewish refugees from Romania to the British Mandate in Palestine.

The ship was hardly seaworthy. Unknown to the desperate passengers it was a wreck that had recently been dredged up from the River Danube. Just three days after it set sail in December, 1941, there was engine failure and the vessel was towed into Istanbul harbour. The British government and the Turkish authorities prevented the cramped passengers from coming ashore.

Finally, on February 23, 1942, Turkish troops boarded the ship and towed it into the Black Sea, leaving it to drift. The passengers hung “Save Us” banners over the sides.

The next day, February 24, (Adar 7, 5702) the Struma was torpedoed and sunk by a Russian submarine. There was only one survivor. It was the largest civilian naval disaster of World War II. Both sides of the conflict share responsibility for the tragic loss of innocent life.

In June, 1942, the British peer Lord Wedgwood spoke of the tragedy in Parliament and argued that Britain had lost the moral right to the Palestine mandate. He said: “I hope yet to live to see those who sent the Struma cargo back to the Nazis hung as high as Haman cheek by jowl with their prototype and Führer, Adolf Hitler.”

Perhaps to different degrees, the Germans, Russians, Turks and British all shared in the responsibility for the 790 deaths.

There is, of course, a world of difference between those immigrants who wish to live according to their culture and traditions, on the one hand, and those who wish to replace or subvert the host culture and its values on the other. There is good reason to be cautious of admitting or nurturing radical elements. My own grandfather, who came here as a refugee, was shipped to Canada as an “enemy alien” to be vetted. He later returned to fight for the British. His parents, who sought to join him, were denied visas and both perished. Throughout his life he retained their plaintive letters requesting that he do what he could to bring them here and secure their lives. His mother, a furrier, would have been content to spend her days cleaning toilets.

We have a humanitarian imperative to look to the welfare of refugees. It neither begins nor ends at our borders, which we legitimately secure. Internationally and on the ground, there must be more work addressing the circumstances which force them to flee their homes. Internally, we need to nurture and integrate immigrants so that they become a part of our society and do not live apart from our society. As we strive for this latter, we must also be mindful of Haman’s manipulation of the self same ideal: palatable language belying evil intent.

While we are rightfully proud of our integration and represent it as a successful model to others, we would be foolish to ignore the manifest and growing anti-Semitism of both left and right wing. We must be vigilant against this and all racism. It would be wrong to imagine that society’s racists would target other religions or cultures, while embracing ours.

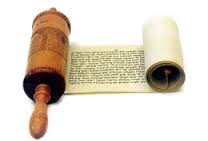

Purim is certainly a celebration of our historic salvation. Within the Megillah we find many cautionary lessons. As Mordechai admonishes Esther, we should not be overly complacent. Sometimes we must take a stand, draw attention and speak out. Perhaps for this were we created.